Khoury College researchers showcase work at CHI 2022

Tue 06.21.22 / Madelaine Millar

Khoury College researchers showcase work at CHI 2022

Tue 06.21.22 / Madelaine Millar

Khoury College researchers showcase work at CHI 2022

Tue 06.21.22 / Madelaine Millar

Khoury College researchers showcase work at CHI 2022

Tue 06.21.22 / Madelaine Millar

The Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, or CHI, is the premier conference in the world of human–computer interaction. Each year, hundreds of papers, workshops, and late-breaking works are accepted, and in 2022, 11 of those works came from Khoury College of Computer Sciences researchers. Their studies cover everything from crowdsourced work and chatbot interactions to supply chain crises and apps to promote Black health. Read on for summaries of their work, or check out the CHI website to learn more.

Interactive Fiction Provotypes for Coping with Interpersonal Racism

or “Creating technology that doesn’t make more problems than it solves”

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Hillary Carey, Riya Shrivastava, Jessica Hammer, Geoff Kaufman — Carnegie Mellon University

In previous studies, To and her colleagues ran workshops where BIPOC imagined and designed racism-navigating technologies. The researchers then distilled those ideas into three provocative prototypes or “provotypes”: a Racism Alarm that blares when racist speech is detected, a Smartwatch Ally that pushes affirming notifications and advice, and a Comfort Speaker that soothes and sympathizes later. If you can spot problems with those ideas, you’ve figured out the point of the study; the question isn’t “can it be built,” but “should it?”

Study participants explored the provotypes through an interactive fiction about a college student navigating microaggressions. In the abstract, BIPOC participants wanted tech tools to help them ascertain that racism had really happened. The Racism Alarm provided certainty, but when it was used in the narrative, participants felt like their privacy had been violated and their agency taken away. The researchers created design recommendations for future racism-related tech, as well as a new process to discover the harm a piece of technology might cause before it hurts real people.

Collecting and Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data in HCI

or “Who cares about race, when, and why?”

- Yiqun T. Chen, Katharina Reinecke — University of Washington

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Angela D. R. Smith — University of Texas at Austin

To and her fellow researchers reviewed CHI proceedings from 2016 to 2021 to determine that just three percent of research on human–computer interaction collects race or ethnicity data from participants (up from 0.1 percent before 2016). Most researchers who collected race or ethnicity data did so because their study was about race or ethnicity.

In those few studies that did ask, about two thirds of participants were white, but noticeably more nonwhite people were included from 2020 onward. Larger studies tend to skew whiter because they often crowdsource using platforms with many white users, like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

So why does that matter? People of different races don’t always interact with the same technology in the same way, but you won’t know that if you don’t know who you’re asking.

Juvenile Graphical Perception: A Comparison between Children and Adults

or “What do kids see when they look at a graph?”

- Liudas Panavas, Tarik Crnovrsanin, Tejas Sathyamurthi, Michelle Borkin, Cody Dunne — Northeastern University

- Amy Worth — Ivy After School Program

- Sara Cordes — Boston College

Fun, colorful graphs are a popular tool for engaging young learners, but do children think about data visualizations the same way adults do?

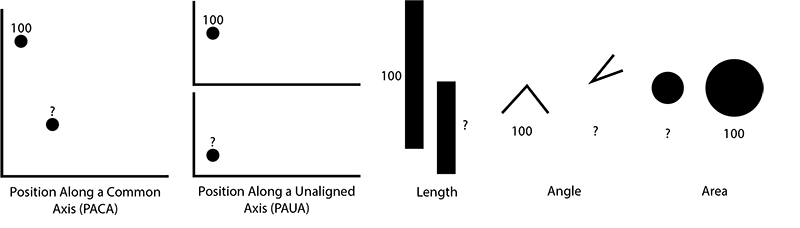

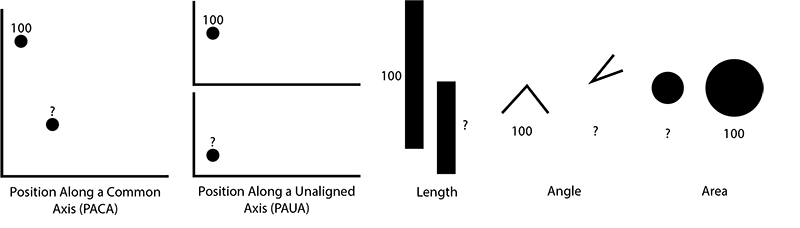

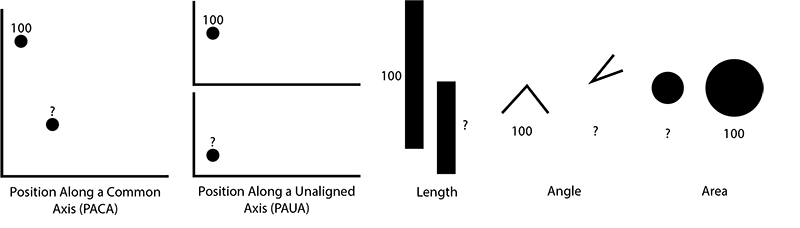

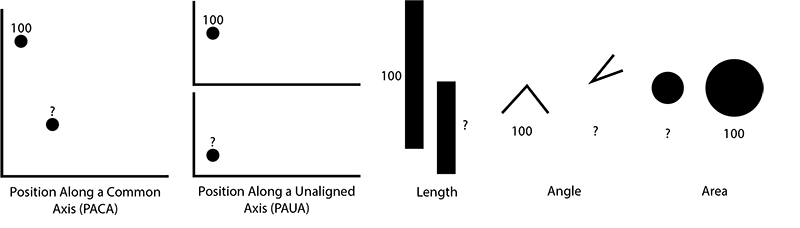

These researchers studied a group of 8-to-12-year-olds and a group of Northeastern students to try to answer that question. The researchers gave both groups the same tasks with age-appropriate instructions; for instance, if a circle is 100 units big, how big is a second, smaller circle? The tasks covered five ways to compare different types of data on a chart: position along a common axis, position along an unaligned axis, area, length, and angle.

Both children and adults gauged relative values the best when looking at two dots on the same graph (like a scatterplot) and least accurate when looking at areas and angles. This means children generally think about data visualizations the same way adults do, just less accurately. The researchers also developed design guidelines for making graphics for kids, including using grid lines to aid accuracy.

How do you Converse with an Analytical Chatbot? Revisiting Gricean Maxims for Designing Analytical Conversational Behavior

or “Talking to Slackbot isn’t like talking to your friends”

- Vidya Setlur — Tableau researcher

- Melanie Tory — Roux Institute, Northeastern University

If you’ve been on the internet for a few years, you’ve probably bamboozled a chatbot with a question a human would have understood just fine.

To learn how to design better chatbots, Setlur and Tory studied how people explore data using chatbots. They did a “Wizard of Oz” study with a researcher behind the curtain pulling the chatbot’s strings, plus a study with actual chatbot prototypes. Study participants explored a data set about the Titanic, asking questions by typing over Slack, chatting aloud with a Bluetooth speaker, or speaking questions to an iPad’s data visualization bot.

The researchers found that while the four Gricean Maxims that govern good communication still applied — responses should be relevant, precise, clear, and concise — people expected more. For instance, a good chatbot should understand the same question phrased differently, and distinguish a follow-up question from a new one. They also found that people use different chatbots differently; when chatting out loud, users tended to ask for simple facts, while visual responses encouraged them to ask “how” and “why.” The researchers concluded with new design guidelines.

To Trust or to Stockpile: Modeling Human-Simulation Interaction in Supply Chain Shortages

or “For those still working through 2020’s toilet paper”

Honorable mention: top five percent of CHI papers

- Omid Mohaddesi, Jacqueline Griffin, Ozlem Ergun, David Kaeli, Stacy Marsella, Casper Harteveld — Northeastern University

Let’s play a game. You’re a pharmaceutical wholesaler; you and your competitor buy medications from two factories and supply them to two hospitals. An algorithm recommends how much you should stock, but one day there’s a crisis at one factory and you’re hit with a shortage. Do you trust the computer system, or do you buy extra just in case? And what if you know exactly how much medicine the factories have left?

The 135 players in the study generally fell into three categories: “hoarders” who bought extra medication from the beginning, “reactors” who bought extra medication once the shortage began, and a much smaller group of “followers” who continued to trust the program. Subjects generally paid less attention to algorithmic recommendations when facing a shortage. The “reactors” and “followers” could be convinced to trust the system when it described the manufacturers’ inventories, but that information made the “hoarders” buy even more as more inventory became available.

The study also presented a new way to use simulation games in studies. The researchers characterized people into groups (reactors, hoarders, and followers) and the supply system into states (stable, supply disruption, and recovering from disruption). By finding common states in dynamic behaviors, they could study the interactions of human and supply chain behaviors.

Effect of Anthropomorphic Glyph Design on the Accuracy of Categorization Tasks

or “Do people sort data better when it’s smiling?”

- Aditeya Pandey, Peter Bex, Michelle Borkin — Northeastern University

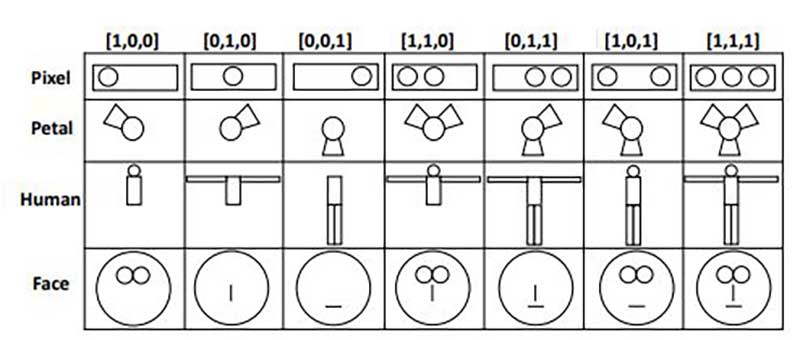

A categorization task is when someone uses multiple features to figure out what something is, like a doctor diagnosing the cause of a headache. While research has shown people better remember data visualizations that look like people, does better recall make for better categorization?

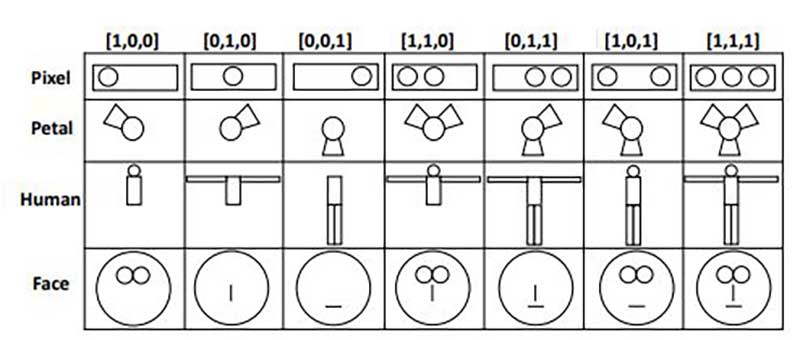

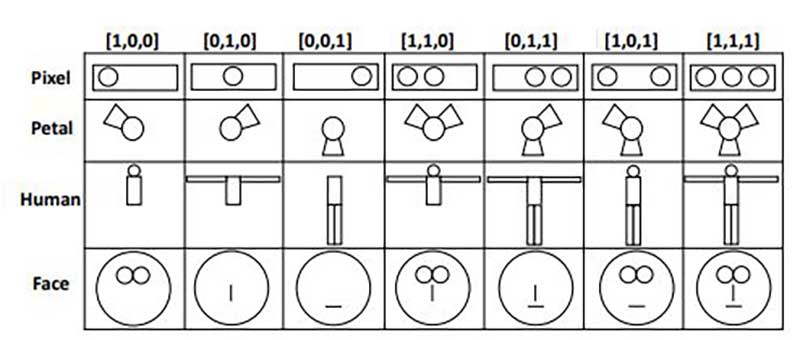

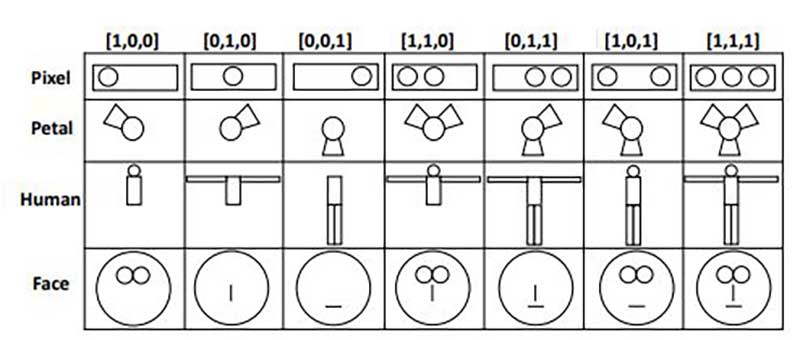

These researchers presented participants with four simple data visualizations; three pixels in a box, a flower, a human figure, and a human face. Each glyph had seven possible permutations; the flower might have only one petal, or the face might be missing eyes and a nose. The researchers categorized the permutations into two families: those with many features (a box with all three pixels) and those with few features (a figure reduced to only a torso). The participants, not knowing what the families were based on, categorized permutations based on their similarity to glyphs already in the family.

The more human-like the glyph, the worse people became at categorizing it. While they easily noticed that boxes with one pixel should go in a different family than boxes with three pixels, participants tended to categorize human-like glyphs based on a single feature, such as whether the face had eyes. As a result, the researchers recommend using human-like visualizations when one element is more important than the rest and avoiding them when all features are equally important.

REGROW: Reimagining Global Crowdsourcing for Better Human-AI Collaboration

or “What could better crowdsourcing look like?”

- Saiph Savage — Northeastern University

- Andy Alorwu, Jonas Oppenlaender, Simo Hosio — University of Oulu

- Niels van Berkel — Aalborg University

- Dmitry Ustalov, Alexey Drutsa — Yandex

- Oliver Bates — Lancaster University

- Danula Hettiachchi — RMIT University

- Ujwal Gadiraju — TU Delft

- Jorge Goncalves — University of Melbourne

Savage’s previous research revealed serious problems with crowdsourced labor. Workers are often paid poorly doing work that doesn’t build skills, and spend many unpaid hours chasing down work and payments. Many workers distrust popular crowdsourcing platforms that don’t provide benefits, firm contracts, or ownership of the worker’s own data.

READ: Faculty research on AI and invisible labor honored for critical real-world impact

In this workshop, researchers from all areas of CHI presented, discussed, refined, and re-presented diverse crowdsourcing improvements. They discussed topics such as using AI to match tasks with workers, improving workers’ flexibility to allocate their time, and the biases within crowd work.

A Virtual Counselor for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling: Adaptive Pedagogy Leads to Greater Knowledge Gain

or “Learning about breast cancer on a budget”

- Shuo Zhou, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

Genetic counseling shows people how likely they are to get certain diseases — in this case, breast cancer — and helps many survive through preventative care or lifestyle changes. Genetic counselors are expensive though, often out of reach for the low-income people at the greatest risk. The researchers wanted to know whether an animated, computer-generated genetic counselor that adapted to a patient’s medical literacy and way of learning could help to fill that gap.

Enter Tanya, a digital counselor who determines things like how much her users already understand, whether they prefer to learn from experts or studies, and whether they prefer visuals or narratives. Then, Tanya tailors a half-hour counseling session to show each woman her risk level and how she can protect herself.

To see if Tanya worked, the researchers had some women use a version of Tanya that didn’t adapt to their needs, or that gave them risk information without really having a conversation. He found that participants learned the most from the fully-featured Tanya and liked her best, although any genetic counseling helped them to learn something.

Community Dynamics in Technospiritual Interventions: Lessons Learned from a Church-based Health Pilot

or “Social media for health and holiness”

- Teresa K O’Leary, Dhaval Parmar, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

- Stefan Olafsson — Reykjavik University

- Michael Paasche-Orlow — Boston University of Medicine

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Institute of Technology

For years, these researchers have worked with Black churches to co-design an app that supports religious Black people’s health. In this four-week study, the researchers put the app ChurchConnect into the hands of two congregations, aiming to refine it further.

ChurchConnect features a digital counselor named Clara who offers everything from scripture and guided meditation to health education, goal-setting help, and counseling. While participants generally liked Clara, they loved the prayer wall, a social-media-style feature where they could request prayers from, and offer support to, fellow community members.

The researchers found that spiritual and social health were big priorities for users, not just physical or mental health. They also identified some problems; for instance, reaching out for prayers publicly can make it obvious when you don’t receive support.

Barriers to Expertise in Citizen Science Games

or “Why no one you know folds proteins for fun”

Josh Aaron Miller, Seth Cooper — Northeastern University

In Foldit, players try to fold proteins into novel structures, which researchers can crowdsource to learn about proteins and potentially incorporate into new medicines. You have to be really good at the game to make anything useful though, and getting good isn’t easy. The same is true of Eterna and Eyewire, which study RNA design and neuron reconstruction. Miller and Cooper wanted to know how people learn these games and what makes them quit, then craft design principles accordingly.

READ: Two game-focused Khoury researchers are turning amateurs into scientists

By talking to Foldit, Eterna, and Eyewire players, they discovered that the path to expertise is a cycle; players learn formally from a tutorial, then from their own exploration, then from other players. Thus, issues such as a limited tutorial, difficult user interface, or exclusive community could drive players away before they gain the expertise to contribute useful designs. The researchers developed guidelines — such as collaborating with professional UI designers and including encouraging social spaces in the game — to help researchers design appealing games.

Shifting Trust: Examining How Trust and Distrust Emerge, Transform, and Collapse in COVID-19 Information Seeking

or “In social media we trust?”

- Yixuan Zhang, Joseph D Gaggiano — Georgia Institute of Technology

- Nurul M Suhaimi, Stacy Marsella, Nutchanon Yongsatianchot, Miso Kim, Jacqueline Griffin — Northeastern University

- Yifan Sun — College of William & Mary

- Shivani A. Patel — Emory University

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Tech & Emory University

Do you trust information from your social media feed? Odds are your answer is more nuanced than it was a few years ago. When a new source of information arises, it takes a while for people to figure out how much to trust it.

These researchers studied how people changed the way they sought information about COVID over time by asking the same questions every two weeks for four months in 2020 through surveys and interviews. They found that people went to social media for coronavirus information less and less over time, both because they didn’t trust the platform and because they didn’t trust the people they followed on it. When people saw conflicting stories on social media, they became frustrated and relied on the platforms less. Over time, participants used social media to learn about COVID less, and those who continued to use it trusted it less, largely because they were afraid they were being exposed to misinformation.

The Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, or CHI, is the premier conference in the world of human–computer interaction. Each year, hundreds of papers, workshops, and late-breaking works are accepted, and in 2022, 11 of those works came from Khoury College of Computer Sciences researchers. Their studies cover everything from crowdsourced work and chatbot interactions to supply chain crises and apps to promote Black health. Read on for summaries of their work, or check out the CHI website to learn more.

Interactive Fiction Provotypes for Coping with Interpersonal Racism

or “Creating technology that doesn’t make more problems than it solves”

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Hillary Carey, Riya Shrivastava, Jessica Hammer, Geoff Kaufman — Carnegie Mellon University

In previous studies, To and her colleagues ran workshops where BIPOC imagined and designed racism-navigating technologies. The researchers then distilled those ideas into three provocative prototypes or “provotypes”: a Racism Alarm that blares when racist speech is detected, a Smartwatch Ally that pushes affirming notifications and advice, and a Comfort Speaker that soothes and sympathizes later. If you can spot problems with those ideas, you’ve figured out the point of the study; the question isn’t “can it be built,” but “should it?”

Study participants explored the provotypes through an interactive fiction about a college student navigating microaggressions. In the abstract, BIPOC participants wanted tech tools to help them ascertain that racism had really happened. The Racism Alarm provided certainty, but when it was used in the narrative, participants felt like their privacy had been violated and their agency taken away. The researchers created design recommendations for future racism-related tech, as well as a new process to discover the harm a piece of technology might cause before it hurts real people.

Collecting and Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data in HCI

or “Who cares about race, when, and why?”

- Yiqun T. Chen, Katharina Reinecke — University of Washington

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Angela D. R. Smith — University of Texas at Austin

To and her fellow researchers reviewed CHI proceedings from 2016 to 2021 to determine that just three percent of research on human–computer interaction collects race or ethnicity data from participants (up from 0.1 percent before 2016). Most researchers who collected race or ethnicity data did so because their study was about race or ethnicity.

In those few studies that did ask, about two thirds of participants were white, but noticeably more nonwhite people were included from 2020 onward. Larger studies tend to skew whiter because they often crowdsource using platforms with many white users, like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

So why does that matter? People of different races don’t always interact with the same technology in the same way, but you won’t know that if you don’t know who you’re asking.

Juvenile Graphical Perception: A Comparison between Children and Adults

or “What do kids see when they look at a graph?”

- Liudas Panavas, Tarik Crnovrsanin, Tejas Sathyamurthi, Michelle Borkin, Cody Dunne — Northeastern University

- Amy Worth — Ivy After School Program

- Sara Cordes — Boston College

Fun, colorful graphs are a popular tool for engaging young learners, but do children think about data visualizations the same way adults do?

These researchers studied a group of 8-to-12-year-olds and a group of Northeastern students to try to answer that question. The researchers gave both groups the same tasks with age-appropriate instructions; for instance, if a circle is 100 units big, how big is a second, smaller circle? The tasks covered five ways to compare different types of data on a chart: position along a common axis, position along an unaligned axis, area, length, and angle.

Both children and adults gauged relative values the best when looking at two dots on the same graph (like a scatterplot) and least accurate when looking at areas and angles. This means children generally think about data visualizations the same way adults do, just less accurately. The researchers also developed design guidelines for making graphics for kids, including using grid lines to aid accuracy.

How do you Converse with an Analytical Chatbot? Revisiting Gricean Maxims for Designing Analytical Conversational Behavior

or “Talking to Slackbot isn’t like talking to your friends”

- Vidya Setlur — Tableau researcher

- Melanie Tory — Roux Institute, Northeastern University

If you’ve been on the internet for a few years, you’ve probably bamboozled a chatbot with a question a human would have understood just fine.

To learn how to design better chatbots, Setlur and Tory studied how people explore data using chatbots. They did a “Wizard of Oz” study with a researcher behind the curtain pulling the chatbot’s strings, plus a study with actual chatbot prototypes. Study participants explored a data set about the Titanic, asking questions by typing over Slack, chatting aloud with a Bluetooth speaker, or speaking questions to an iPad’s data visualization bot.

The researchers found that while the four Gricean Maxims that govern good communication still applied — responses should be relevant, precise, clear, and concise — people expected more. For instance, a good chatbot should understand the same question phrased differently, and distinguish a follow-up question from a new one. They also found that people use different chatbots differently; when chatting out loud, users tended to ask for simple facts, while visual responses encouraged them to ask “how” and “why.” The researchers concluded with new design guidelines.

To Trust or to Stockpile: Modeling Human-Simulation Interaction in Supply Chain Shortages

or “For those still working through 2020’s toilet paper”

Honorable mention: top five percent of CHI papers

- Omid Mohaddesi, Jacqueline Griffin, Ozlem Ergun, David Kaeli, Stacy Marsella, Casper Harteveld — Northeastern University

Let’s play a game. You’re a pharmaceutical wholesaler; you and your competitor buy medications from two factories and supply them to two hospitals. An algorithm recommends how much you should stock, but one day there’s a crisis at one factory and you’re hit with a shortage. Do you trust the computer system, or do you buy extra just in case? And what if you know exactly how much medicine the factories have left?

The 135 players in the study generally fell into three categories: “hoarders” who bought extra medication from the beginning, “reactors” who bought extra medication once the shortage began, and a much smaller group of “followers” who continued to trust the program. Subjects generally paid less attention to algorithmic recommendations when facing a shortage. The “reactors” and “followers” could be convinced to trust the system when it described the manufacturers’ inventories, but that information made the “hoarders” buy even more as more inventory became available.

The study also presented a new way to use simulation games in studies. The researchers characterized people into groups (reactors, hoarders, and followers) and the supply system into states (stable, supply disruption, and recovering from disruption). By finding common states in dynamic behaviors, they could study the interactions of human and supply chain behaviors.

Effect of Anthropomorphic Glyph Design on the Accuracy of Categorization Tasks

or “Do people sort data better when it’s smiling?”

- Aditeya Pandey, Peter Bex, Michelle Borkin — Northeastern University

A categorization task is when someone uses multiple features to figure out what something is, like a doctor diagnosing the cause of a headache. While research has shown people better remember data visualizations that look like people, does better recall make for better categorization?

These researchers presented participants with four simple data visualizations; three pixels in a box, a flower, a human figure, and a human face. Each glyph had seven possible permutations; the flower might have only one petal, or the face might be missing eyes and a nose. The researchers categorized the permutations into two families: those with many features (a box with all three pixels) and those with few features (a figure reduced to only a torso). The participants, not knowing what the families were based on, categorized permutations based on their similarity to glyphs already in the family.

The more human-like the glyph, the worse people became at categorizing it. While they easily noticed that boxes with one pixel should go in a different family than boxes with three pixels, participants tended to categorize human-like glyphs based on a single feature, such as whether the face had eyes. As a result, the researchers recommend using human-like visualizations when one element is more important than the rest and avoiding them when all features are equally important.

REGROW: Reimagining Global Crowdsourcing for Better Human-AI Collaboration

or “What could better crowdsourcing look like?”

- Saiph Savage — Northeastern University

- Andy Alorwu, Jonas Oppenlaender, Simo Hosio — University of Oulu

- Niels van Berkel — Aalborg University

- Dmitry Ustalov, Alexey Drutsa — Yandex

- Oliver Bates — Lancaster University

- Danula Hettiachchi — RMIT University

- Ujwal Gadiraju — TU Delft

- Jorge Goncalves — University of Melbourne

Savage’s previous research revealed serious problems with crowdsourced labor. Workers are often paid poorly doing work that doesn’t build skills, and spend many unpaid hours chasing down work and payments. Many workers distrust popular crowdsourcing platforms that don’t provide benefits, firm contracts, or ownership of the worker’s own data.

READ: Faculty research on AI and invisible labor honored for critical real-world impact

In this workshop, researchers from all areas of CHI presented, discussed, refined, and re-presented diverse crowdsourcing improvements. They discussed topics such as using AI to match tasks with workers, improving workers’ flexibility to allocate their time, and the biases within crowd work.

A Virtual Counselor for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling: Adaptive Pedagogy Leads to Greater Knowledge Gain

or “Learning about breast cancer on a budget”

- Shuo Zhou, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

Genetic counseling shows people how likely they are to get certain diseases — in this case, breast cancer — and helps many survive through preventative care or lifestyle changes. Genetic counselors are expensive though, often out of reach for the low-income people at the greatest risk. The researchers wanted to know whether an animated, computer-generated genetic counselor that adapted to a patient’s medical literacy and way of learning could help to fill that gap.

Enter Tanya, a digital counselor who determines things like how much her users already understand, whether they prefer to learn from experts or studies, and whether they prefer visuals or narratives. Then, Tanya tailors a half-hour counseling session to show each woman her risk level and how she can protect herself.

To see if Tanya worked, the researchers had some women use a version of Tanya that didn’t adapt to their needs, or that gave them risk information without really having a conversation. He found that participants learned the most from the fully-featured Tanya and liked her best, although any genetic counseling helped them to learn something.

Community Dynamics in Technospiritual Interventions: Lessons Learned from a Church-based Health Pilot

or “Social media for health and holiness”

- Teresa K O’Leary, Dhaval Parmar, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

- Stefan Olafsson — Reykjavik University

- Michael Paasche-Orlow — Boston University of Medicine

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Institute of Technology

For years, these researchers have worked with Black churches to co-design an app that supports religious Black people’s health. In this four-week study, the researchers put the app ChurchConnect into the hands of two congregations, aiming to refine it further.

ChurchConnect features a digital counselor named Clara who offers everything from scripture and guided meditation to health education, goal-setting help, and counseling. While participants generally liked Clara, they loved the prayer wall, a social-media-style feature where they could request prayers from, and offer support to, fellow community members.

The researchers found that spiritual and social health were big priorities for users, not just physical or mental health. They also identified some problems; for instance, reaching out for prayers publicly can make it obvious when you don’t receive support.

Barriers to Expertise in Citizen Science Games

or “Why no one you know folds proteins for fun”

Josh Aaron Miller, Seth Cooper — Northeastern University

In Foldit, players try to fold proteins into novel structures, which researchers can crowdsource to learn about proteins and potentially incorporate into new medicines. You have to be really good at the game to make anything useful though, and getting good isn’t easy. The same is true of Eterna and Eyewire, which study RNA design and neuron reconstruction. Miller and Cooper wanted to know how people learn these games and what makes them quit, then craft design principles accordingly.

READ: Two game-focused Khoury researchers are turning amateurs into scientists

By talking to Foldit, Eterna, and Eyewire players, they discovered that the path to expertise is a cycle; players learn formally from a tutorial, then from their own exploration, then from other players. Thus, issues such as a limited tutorial, difficult user interface, or exclusive community could drive players away before they gain the expertise to contribute useful designs. The researchers developed guidelines — such as collaborating with professional UI designers and including encouraging social spaces in the game — to help researchers design appealing games.

Shifting Trust: Examining How Trust and Distrust Emerge, Transform, and Collapse in COVID-19 Information Seeking

or “In social media we trust?”

- Yixuan Zhang, Joseph D Gaggiano — Georgia Institute of Technology

- Nurul M Suhaimi, Stacy Marsella, Nutchanon Yongsatianchot, Miso Kim, Jacqueline Griffin — Northeastern University

- Yifan Sun — College of William & Mary

- Shivani A. Patel — Emory University

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Tech & Emory University

Do you trust information from your social media feed? Odds are your answer is more nuanced than it was a few years ago. When a new source of information arises, it takes a while for people to figure out how much to trust it.

These researchers studied how people changed the way they sought information about COVID over time by asking the same questions every two weeks for four months in 2020 through surveys and interviews. They found that people went to social media for coronavirus information less and less over time, both because they didn’t trust the platform and because they didn’t trust the people they followed on it. When people saw conflicting stories on social media, they became frustrated and relied on the platforms less. Over time, participants used social media to learn about COVID less, and those who continued to use it trusted it less, largely because they were afraid they were being exposed to misinformation.

The Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, or CHI, is the premier conference in the world of human–computer interaction. Each year, hundreds of papers, workshops, and late-breaking works are accepted, and in 2022, 11 of those works came from Khoury College of Computer Sciences researchers. Their studies cover everything from crowdsourced work and chatbot interactions to supply chain crises and apps to promote Black health. Read on for summaries of their work, or check out the CHI website to learn more.

Interactive Fiction Provotypes for Coping with Interpersonal Racism

or “Creating technology that doesn’t make more problems than it solves”

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Hillary Carey, Riya Shrivastava, Jessica Hammer, Geoff Kaufman — Carnegie Mellon University

In previous studies, To and her colleagues ran workshops where BIPOC imagined and designed racism-navigating technologies. The researchers then distilled those ideas into three provocative prototypes or “provotypes”: a Racism Alarm that blares when racist speech is detected, a Smartwatch Ally that pushes affirming notifications and advice, and a Comfort Speaker that soothes and sympathizes later. If you can spot problems with those ideas, you’ve figured out the point of the study; the question isn’t “can it be built,” but “should it?”

Study participants explored the provotypes through an interactive fiction about a college student navigating microaggressions. In the abstract, BIPOC participants wanted tech tools to help them ascertain that racism had really happened. The Racism Alarm provided certainty, but when it was used in the narrative, participants felt like their privacy had been violated and their agency taken away. The researchers created design recommendations for future racism-related tech, as well as a new process to discover the harm a piece of technology might cause before it hurts real people.

Collecting and Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data in HCI

or “Who cares about race, when, and why?”

- Yiqun T. Chen, Katharina Reinecke — University of Washington

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Angela D. R. Smith — University of Texas at Austin

To and her fellow researchers reviewed CHI proceedings from 2016 to 2021 to determine that just three percent of research on human–computer interaction collects race or ethnicity data from participants (up from 0.1 percent before 2016). Most researchers who collected race or ethnicity data did so because their study was about race or ethnicity.

In those few studies that did ask, about two thirds of participants were white, but noticeably more nonwhite people were included from 2020 onward. Larger studies tend to skew whiter because they often crowdsource using platforms with many white users, like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

So why does that matter? People of different races don’t always interact with the same technology in the same way, but you won’t know that if you don’t know who you’re asking.

Juvenile Graphical Perception: A Comparison between Children and Adults

or “What do kids see when they look at a graph?”

- Liudas Panavas, Tarik Crnovrsanin, Tejas Sathyamurthi, Michelle Borkin, Cody Dunne — Northeastern University

- Amy Worth — Ivy After School Program

- Sara Cordes — Boston College

Fun, colorful graphs are a popular tool for engaging young learners, but do children think about data visualizations the same way adults do?

These researchers studied a group of 8-to-12-year-olds and a group of Northeastern students to try to answer that question. The researchers gave both groups the same tasks with age-appropriate instructions; for instance, if a circle is 100 units big, how big is a second, smaller circle? The tasks covered five ways to compare different types of data on a chart: position along a common axis, position along an unaligned axis, area, length, and angle.

Both children and adults gauged relative values the best when looking at two dots on the same graph (like a scatterplot) and least accurate when looking at areas and angles. This means children generally think about data visualizations the same way adults do, just less accurately. The researchers also developed design guidelines for making graphics for kids, including using grid lines to aid accuracy.

How do you Converse with an Analytical Chatbot? Revisiting Gricean Maxims for Designing Analytical Conversational Behavior

or “Talking to Slackbot isn’t like talking to your friends”

- Vidya Setlur — Tableau researcher

- Melanie Tory — Roux Institute, Northeastern University

If you’ve been on the internet for a few years, you’ve probably bamboozled a chatbot with a question a human would have understood just fine.

To learn how to design better chatbots, Setlur and Tory studied how people explore data using chatbots. They did a “Wizard of Oz” study with a researcher behind the curtain pulling the chatbot’s strings, plus a study with actual chatbot prototypes. Study participants explored a data set about the Titanic, asking questions by typing over Slack, chatting aloud with a Bluetooth speaker, or speaking questions to an iPad’s data visualization bot.

The researchers found that while the four Gricean Maxims that govern good communication still applied — responses should be relevant, precise, clear, and concise — people expected more. For instance, a good chatbot should understand the same question phrased differently, and distinguish a follow-up question from a new one. They also found that people use different chatbots differently; when chatting out loud, users tended to ask for simple facts, while visual responses encouraged them to ask “how” and “why.” The researchers concluded with new design guidelines.

To Trust or to Stockpile: Modeling Human-Simulation Interaction in Supply Chain Shortages

or “For those still working through 2020’s toilet paper”

Honorable mention: top five percent of CHI papers

- Omid Mohaddesi, Jacqueline Griffin, Ozlem Ergun, David Kaeli, Stacy Marsella, Casper Harteveld — Northeastern University

Let’s play a game. You’re a pharmaceutical wholesaler; you and your competitor buy medications from two factories and supply them to two hospitals. An algorithm recommends how much you should stock, but one day there’s a crisis at one factory and you’re hit with a shortage. Do you trust the computer system, or do you buy extra just in case? And what if you know exactly how much medicine the factories have left?

The 135 players in the study generally fell into three categories: “hoarders” who bought extra medication from the beginning, “reactors” who bought extra medication once the shortage began, and a much smaller group of “followers” who continued to trust the program. Subjects generally paid less attention to algorithmic recommendations when facing a shortage. The “reactors” and “followers” could be convinced to trust the system when it described the manufacturers’ inventories, but that information made the “hoarders” buy even more as more inventory became available.

The study also presented a new way to use simulation games in studies. The researchers characterized people into groups (reactors, hoarders, and followers) and the supply system into states (stable, supply disruption, and recovering from disruption). By finding common states in dynamic behaviors, they could study the interactions of human and supply chain behaviors.

Effect of Anthropomorphic Glyph Design on the Accuracy of Categorization Tasks

or “Do people sort data better when it’s smiling?”

- Aditeya Pandey, Peter Bex, Michelle Borkin — Northeastern University

A categorization task is when someone uses multiple features to figure out what something is, like a doctor diagnosing the cause of a headache. While research has shown people better remember data visualizations that look like people, does better recall make for better categorization?

These researchers presented participants with four simple data visualizations; three pixels in a box, a flower, a human figure, and a human face. Each glyph had seven possible permutations; the flower might have only one petal, or the face might be missing eyes and a nose. The researchers categorized the permutations into two families: those with many features (a box with all three pixels) and those with few features (a figure reduced to only a torso). The participants, not knowing what the families were based on, categorized permutations based on their similarity to glyphs already in the family.

The more human-like the glyph, the worse people became at categorizing it. While they easily noticed that boxes with one pixel should go in a different family than boxes with three pixels, participants tended to categorize human-like glyphs based on a single feature, such as whether the face had eyes. As a result, the researchers recommend using human-like visualizations when one element is more important than the rest and avoiding them when all features are equally important.

REGROW: Reimagining Global Crowdsourcing for Better Human-AI Collaboration

or “What could better crowdsourcing look like?”

- Saiph Savage — Northeastern University

- Andy Alorwu, Jonas Oppenlaender, Simo Hosio — University of Oulu

- Niels van Berkel — Aalborg University

- Dmitry Ustalov, Alexey Drutsa — Yandex

- Oliver Bates — Lancaster University

- Danula Hettiachchi — RMIT University

- Ujwal Gadiraju — TU Delft

- Jorge Goncalves — University of Melbourne

Savage’s previous research revealed serious problems with crowdsourced labor. Workers are often paid poorly doing work that doesn’t build skills, and spend many unpaid hours chasing down work and payments. Many workers distrust popular crowdsourcing platforms that don’t provide benefits, firm contracts, or ownership of the worker’s own data.

READ: Faculty research on AI and invisible labor honored for critical real-world impact

In this workshop, researchers from all areas of CHI presented, discussed, refined, and re-presented diverse crowdsourcing improvements. They discussed topics such as using AI to match tasks with workers, improving workers’ flexibility to allocate their time, and the biases within crowd work.

A Virtual Counselor for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling: Adaptive Pedagogy Leads to Greater Knowledge Gain

or “Learning about breast cancer on a budget”

- Shuo Zhou, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

Genetic counseling shows people how likely they are to get certain diseases — in this case, breast cancer — and helps many survive through preventative care or lifestyle changes. Genetic counselors are expensive though, often out of reach for the low-income people at the greatest risk. The researchers wanted to know whether an animated, computer-generated genetic counselor that adapted to a patient’s medical literacy and way of learning could help to fill that gap.

Enter Tanya, a digital counselor who determines things like how much her users already understand, whether they prefer to learn from experts or studies, and whether they prefer visuals or narratives. Then, Tanya tailors a half-hour counseling session to show each woman her risk level and how she can protect herself.

To see if Tanya worked, the researchers had some women use a version of Tanya that didn’t adapt to their needs, or that gave them risk information without really having a conversation. He found that participants learned the most from the fully-featured Tanya and liked her best, although any genetic counseling helped them to learn something.

Community Dynamics in Technospiritual Interventions: Lessons Learned from a Church-based Health Pilot

or “Social media for health and holiness”

- Teresa K O’Leary, Dhaval Parmar, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

- Stefan Olafsson — Reykjavik University

- Michael Paasche-Orlow — Boston University of Medicine

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Institute of Technology

For years, these researchers have worked with Black churches to co-design an app that supports religious Black people’s health. In this four-week study, the researchers put the app ChurchConnect into the hands of two congregations, aiming to refine it further.

ChurchConnect features a digital counselor named Clara who offers everything from scripture and guided meditation to health education, goal-setting help, and counseling. While participants generally liked Clara, they loved the prayer wall, a social-media-style feature where they could request prayers from, and offer support to, fellow community members.

The researchers found that spiritual and social health were big priorities for users, not just physical or mental health. They also identified some problems; for instance, reaching out for prayers publicly can make it obvious when you don’t receive support.

Barriers to Expertise in Citizen Science Games

or “Why no one you know folds proteins for fun”

Josh Aaron Miller, Seth Cooper — Northeastern University

In Foldit, players try to fold proteins into novel structures, which researchers can crowdsource to learn about proteins and potentially incorporate into new medicines. You have to be really good at the game to make anything useful though, and getting good isn’t easy. The same is true of Eterna and Eyewire, which study RNA design and neuron reconstruction. Miller and Cooper wanted to know how people learn these games and what makes them quit, then craft design principles accordingly.

READ: Two game-focused Khoury researchers are turning amateurs into scientists

By talking to Foldit, Eterna, and Eyewire players, they discovered that the path to expertise is a cycle; players learn formally from a tutorial, then from their own exploration, then from other players. Thus, issues such as a limited tutorial, difficult user interface, or exclusive community could drive players away before they gain the expertise to contribute useful designs. The researchers developed guidelines — such as collaborating with professional UI designers and including encouraging social spaces in the game — to help researchers design appealing games.

Shifting Trust: Examining How Trust and Distrust Emerge, Transform, and Collapse in COVID-19 Information Seeking

or “In social media we trust?”

- Yixuan Zhang, Joseph D Gaggiano — Georgia Institute of Technology

- Nurul M Suhaimi, Stacy Marsella, Nutchanon Yongsatianchot, Miso Kim, Jacqueline Griffin — Northeastern University

- Yifan Sun — College of William & Mary

- Shivani A. Patel — Emory University

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Tech & Emory University

Do you trust information from your social media feed? Odds are your answer is more nuanced than it was a few years ago. When a new source of information arises, it takes a while for people to figure out how much to trust it.

These researchers studied how people changed the way they sought information about COVID over time by asking the same questions every two weeks for four months in 2020 through surveys and interviews. They found that people went to social media for coronavirus information less and less over time, both because they didn’t trust the platform and because they didn’t trust the people they followed on it. When people saw conflicting stories on social media, they became frustrated and relied on the platforms less. Over time, participants used social media to learn about COVID less, and those who continued to use it trusted it less, largely because they were afraid they were being exposed to misinformation.

The Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, or CHI, is the premier conference in the world of human–computer interaction. Each year, hundreds of papers, workshops, and late-breaking works are accepted, and in 2022, 11 of those works came from Khoury College of Computer Sciences researchers. Their studies cover everything from crowdsourced work and chatbot interactions to supply chain crises and apps to promote Black health. Read on for summaries of their work, or check out the CHI website to learn more.

Interactive Fiction Provotypes for Coping with Interpersonal Racism

or “Creating technology that doesn’t make more problems than it solves”

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Hillary Carey, Riya Shrivastava, Jessica Hammer, Geoff Kaufman — Carnegie Mellon University

In previous studies, To and her colleagues ran workshops where BIPOC imagined and designed racism-navigating technologies. The researchers then distilled those ideas into three provocative prototypes or “provotypes”: a Racism Alarm that blares when racist speech is detected, a Smartwatch Ally that pushes affirming notifications and advice, and a Comfort Speaker that soothes and sympathizes later. If you can spot problems with those ideas, you’ve figured out the point of the study; the question isn’t “can it be built,” but “should it?”

Study participants explored the provotypes through an interactive fiction about a college student navigating microaggressions. In the abstract, BIPOC participants wanted tech tools to help them ascertain that racism had really happened. The Racism Alarm provided certainty, but when it was used in the narrative, participants felt like their privacy had been violated and their agency taken away. The researchers created design recommendations for future racism-related tech, as well as a new process to discover the harm a piece of technology might cause before it hurts real people.

Collecting and Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data in HCI

or “Who cares about race, when, and why?”

- Yiqun T. Chen, Katharina Reinecke — University of Washington

- Alexandra To — Northeastern University

- Angela D. R. Smith — University of Texas at Austin

To and her fellow researchers reviewed CHI proceedings from 2016 to 2021 to determine that just three percent of research on human–computer interaction collects race or ethnicity data from participants (up from 0.1 percent before 2016). Most researchers who collected race or ethnicity data did so because their study was about race or ethnicity.

In those few studies that did ask, about two thirds of participants were white, but noticeably more nonwhite people were included from 2020 onward. Larger studies tend to skew whiter because they often crowdsource using platforms with many white users, like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

So why does that matter? People of different races don’t always interact with the same technology in the same way, but you won’t know that if you don’t know who you’re asking.

Juvenile Graphical Perception: A Comparison between Children and Adults

or “What do kids see when they look at a graph?”

- Liudas Panavas, Tarik Crnovrsanin, Tejas Sathyamurthi, Michelle Borkin, Cody Dunne — Northeastern University

- Amy Worth — Ivy After School Program

- Sara Cordes — Boston College

Fun, colorful graphs are a popular tool for engaging young learners, but do children think about data visualizations the same way adults do?

These researchers studied a group of 8-to-12-year-olds and a group of Northeastern students to try to answer that question. The researchers gave both groups the same tasks with age-appropriate instructions; for instance, if a circle is 100 units big, how big is a second, smaller circle? The tasks covered five ways to compare different types of data on a chart: position along a common axis, position along an unaligned axis, area, length, and angle.

Both children and adults gauged relative values the best when looking at two dots on the same graph (like a scatterplot) and least accurate when looking at areas and angles. This means children generally think about data visualizations the same way adults do, just less accurately. The researchers also developed design guidelines for making graphics for kids, including using grid lines to aid accuracy.

How do you Converse with an Analytical Chatbot? Revisiting Gricean Maxims for Designing Analytical Conversational Behavior

or “Talking to Slackbot isn’t like talking to your friends”

- Vidya Setlur — Tableau researcher

- Melanie Tory — Roux Institute, Northeastern University

If you’ve been on the internet for a few years, you’ve probably bamboozled a chatbot with a question a human would have understood just fine.

To learn how to design better chatbots, Setlur and Tory studied how people explore data using chatbots. They did a “Wizard of Oz” study with a researcher behind the curtain pulling the chatbot’s strings, plus a study with actual chatbot prototypes. Study participants explored a data set about the Titanic, asking questions by typing over Slack, chatting aloud with a Bluetooth speaker, or speaking questions to an iPad’s data visualization bot.

The researchers found that while the four Gricean Maxims that govern good communication still applied — responses should be relevant, precise, clear, and concise — people expected more. For instance, a good chatbot should understand the same question phrased differently, and distinguish a follow-up question from a new one. They also found that people use different chatbots differently; when chatting out loud, users tended to ask for simple facts, while visual responses encouraged them to ask “how” and “why.” The researchers concluded with new design guidelines.

To Trust or to Stockpile: Modeling Human-Simulation Interaction in Supply Chain Shortages

or “For those still working through 2020’s toilet paper”

Honorable mention: top five percent of CHI papers

- Omid Mohaddesi, Jacqueline Griffin, Ozlem Ergun, David Kaeli, Stacy Marsella, Casper Harteveld — Northeastern University

Let’s play a game. You’re a pharmaceutical wholesaler; you and your competitor buy medications from two factories and supply them to two hospitals. An algorithm recommends how much you should stock, but one day there’s a crisis at one factory and you’re hit with a shortage. Do you trust the computer system, or do you buy extra just in case? And what if you know exactly how much medicine the factories have left?

The 135 players in the study generally fell into three categories: “hoarders” who bought extra medication from the beginning, “reactors” who bought extra medication once the shortage began, and a much smaller group of “followers” who continued to trust the program. Subjects generally paid less attention to algorithmic recommendations when facing a shortage. The “reactors” and “followers” could be convinced to trust the system when it described the manufacturers’ inventories, but that information made the “hoarders” buy even more as more inventory became available.

The study also presented a new way to use simulation games in studies. The researchers characterized people into groups (reactors, hoarders, and followers) and the supply system into states (stable, supply disruption, and recovering from disruption). By finding common states in dynamic behaviors, they could study the interactions of human and supply chain behaviors.

Effect of Anthropomorphic Glyph Design on the Accuracy of Categorization Tasks

or “Do people sort data better when it’s smiling?”

- Aditeya Pandey, Peter Bex, Michelle Borkin — Northeastern University

A categorization task is when someone uses multiple features to figure out what something is, like a doctor diagnosing the cause of a headache. While research has shown people better remember data visualizations that look like people, does better recall make for better categorization?

These researchers presented participants with four simple data visualizations; three pixels in a box, a flower, a human figure, and a human face. Each glyph had seven possible permutations; the flower might have only one petal, or the face might be missing eyes and a nose. The researchers categorized the permutations into two families: those with many features (a box with all three pixels) and those with few features (a figure reduced to only a torso). The participants, not knowing what the families were based on, categorized permutations based on their similarity to glyphs already in the family.

The more human-like the glyph, the worse people became at categorizing it. While they easily noticed that boxes with one pixel should go in a different family than boxes with three pixels, participants tended to categorize human-like glyphs based on a single feature, such as whether the face had eyes. As a result, the researchers recommend using human-like visualizations when one element is more important than the rest and avoiding them when all features are equally important.

REGROW: Reimagining Global Crowdsourcing for Better Human-AI Collaboration

or “What could better crowdsourcing look like?”

- Saiph Savage — Northeastern University

- Andy Alorwu, Jonas Oppenlaender, Simo Hosio — University of Oulu

- Niels van Berkel — Aalborg University

- Dmitry Ustalov, Alexey Drutsa — Yandex

- Oliver Bates — Lancaster University

- Danula Hettiachchi — RMIT University

- Ujwal Gadiraju — TU Delft

- Jorge Goncalves — University of Melbourne

Savage’s previous research revealed serious problems with crowdsourced labor. Workers are often paid poorly doing work that doesn’t build skills, and spend many unpaid hours chasing down work and payments. Many workers distrust popular crowdsourcing platforms that don’t provide benefits, firm contracts, or ownership of the worker’s own data.

READ: Faculty research on AI and invisible labor honored for critical real-world impact

In this workshop, researchers from all areas of CHI presented, discussed, refined, and re-presented diverse crowdsourcing improvements. They discussed topics such as using AI to match tasks with workers, improving workers’ flexibility to allocate their time, and the biases within crowd work.

A Virtual Counselor for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling: Adaptive Pedagogy Leads to Greater Knowledge Gain

or “Learning about breast cancer on a budget”

- Shuo Zhou, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

Genetic counseling shows people how likely they are to get certain diseases — in this case, breast cancer — and helps many survive through preventative care or lifestyle changes. Genetic counselors are expensive though, often out of reach for the low-income people at the greatest risk. The researchers wanted to know whether an animated, computer-generated genetic counselor that adapted to a patient’s medical literacy and way of learning could help to fill that gap.

Enter Tanya, a digital counselor who determines things like how much her users already understand, whether they prefer to learn from experts or studies, and whether they prefer visuals or narratives. Then, Tanya tailors a half-hour counseling session to show each woman her risk level and how she can protect herself.

To see if Tanya worked, the researchers had some women use a version of Tanya that didn’t adapt to their needs, or that gave them risk information without really having a conversation. He found that participants learned the most from the fully-featured Tanya and liked her best, although any genetic counseling helped them to learn something.

Community Dynamics in Technospiritual Interventions: Lessons Learned from a Church-based Health Pilot

or “Social media for health and holiness”

- Teresa K O’Leary, Dhaval Parmar, Timothy Bickmore — Northeastern University

- Stefan Olafsson — Reykjavik University

- Michael Paasche-Orlow — Boston University of Medicine

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Institute of Technology

For years, these researchers have worked with Black churches to co-design an app that supports religious Black people’s health. In this four-week study, the researchers put the app ChurchConnect into the hands of two congregations, aiming to refine it further.

ChurchConnect features a digital counselor named Clara who offers everything from scripture and guided meditation to health education, goal-setting help, and counseling. While participants generally liked Clara, they loved the prayer wall, a social-media-style feature where they could request prayers from, and offer support to, fellow community members.

The researchers found that spiritual and social health were big priorities for users, not just physical or mental health. They also identified some problems; for instance, reaching out for prayers publicly can make it obvious when you don’t receive support.

Barriers to Expertise in Citizen Science Games

or “Why no one you know folds proteins for fun”

Josh Aaron Miller, Seth Cooper — Northeastern University

In Foldit, players try to fold proteins into novel structures, which researchers can crowdsource to learn about proteins and potentially incorporate into new medicines. You have to be really good at the game to make anything useful though, and getting good isn’t easy. The same is true of Eterna and Eyewire, which study RNA design and neuron reconstruction. Miller and Cooper wanted to know how people learn these games and what makes them quit, then craft design principles accordingly.

READ: Two game-focused Khoury researchers are turning amateurs into scientists

By talking to Foldit, Eterna, and Eyewire players, they discovered that the path to expertise is a cycle; players learn formally from a tutorial, then from their own exploration, then from other players. Thus, issues such as a limited tutorial, difficult user interface, or exclusive community could drive players away before they gain the expertise to contribute useful designs. The researchers developed guidelines — such as collaborating with professional UI designers and including encouraging social spaces in the game — to help researchers design appealing games.

Shifting Trust: Examining How Trust and Distrust Emerge, Transform, and Collapse in COVID-19 Information Seeking

or “In social media we trust?”

- Yixuan Zhang, Joseph D Gaggiano — Georgia Institute of Technology

- Nurul M Suhaimi, Stacy Marsella, Nutchanon Yongsatianchot, Miso Kim, Jacqueline Griffin — Northeastern University

- Yifan Sun — College of William & Mary

- Shivani A. Patel — Emory University

- Andrea G Parker — Georgia Tech & Emory University

Do you trust information from your social media feed? Odds are your answer is more nuanced than it was a few years ago. When a new source of information arises, it takes a while for people to figure out how much to trust it.

These researchers studied how people changed the way they sought information about COVID over time by asking the same questions every two weeks for four months in 2020 through surveys and interviews. They found that people went to social media for coronavirus information less and less over time, both because they didn’t trust the platform and because they didn’t trust the people they followed on it. When people saw conflicting stories on social media, they became frustrated and relied on the platforms less. Over time, participants used social media to learn about COVID less, and those who continued to use it trusted it less, largely because they were afraid they were being exposed to misinformation.